|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

M

a y 2 0 0 4

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Critical i

State

of Affairs, Lindsay Bowdoin Key,

Another reason is to step back and take stock of these ridiculous times by casting the net wider than the often-incestuous vacuum of gallery culture. Still, April in the Portland art scene was noteworthy because of the many social bellwether shows, like State of Affairs at Savage Art Resources or Lindsay Bowdoin Key at Haze. It's both wartime and election time here (presidential and mayoral, for those reading outside Portland's ramparts). I often question whether Portland is a black sheep or another member of the herd of American cities. The recent spate of now-legalized same-sex marriages in Portland indicates darker sheep. As a city-state, PDX has rarely toed the line with other American urban centers and is a particularly good place to be when questioning the place of the United States in the grand scheme of things. The discussion absolutely needs to take place.

The world, as usual, is in chaos. But there customarily is a certain professionalism to being an Ugly American that is utterly missing these days. Our foreign policy and related actions remind me of the ancient Athenians' infamous and ill-fated Sicilian campaign. Overconfidence and oversimplification were the main problems there, too. (My opinion on this is more of an operational evaluation than a political statement.) Net result: it's pretty much Greek tragedy and in the cafés of Portland there is a lot of unrest. At my favorite coffeehouse, Anna Bananas in Northwest Portland's Alphabet District, Joel Preston Smith displayed some nice war photography. Most possessed the combination of beauty and repulsion usually accompanying that genre of photojournalism when done well. The restlessness is being articulated in demographically engaged works, too. Ben Hull's "Mid-Life" at Ogle is one of those rare sociological commentaries made through formalist abstraction about baby boomers.

"Mid-Life" is a tensioned graft of metal, wire and wood, like an Anish Kapoor car rack that peels back to reveal wooden surfboard/candy bar planks. The materials indicate youth beneath the slick navy-blue exterior. Pun intended, "Mid-Life" is a very timely work. I like how it is not just an indictment of the Miata-driving bald guy with an insecure girlfriend 15-25 years his junior who needs a daddy figure. Instead, it seems to celebrate youth. And who can blame the boomers? Youth is wasted on the young, but that's the enviable luxury. It's odd to think of how baby boomers value youth as a commodity. Yet, I wonder how much many of them value youth in general as people. (It works both ways; how many Gen-Y-ers appreciate anyone over 40?) I can say one thing: Anyone who collects art should get to know youth through face-to-face exchanges. "Mid-Life" does not necessarily condemn the mid-life crisis – maybe it's a good kind of crisis? Hold still, please!

The most poignant piece I saw in April was Brian Borrello's "Shoes (for standing absolutely still)." Sometimes when the world gets crazy it's best to take a time out. These are very Zen and definitely male shoes. Of course, Borrello, a new father, is learning to fill new shoes, and what could be more profound than watching the cycle of life continue? War awareness and parenting do not initially seem too related, but they are. For example, there is no more lasting and palpable grief than that of a parent who outlives their child. A second net result of being responsible for another person's life is you suddenly understand the value of life a lot more.

No, I am not going suburban here and, no, I am not a father. But when women special to me have had children, I have felt a tiny sample of this fatherly stillness. Gilles Foisy's excellent show at Butters Gallery consistently carried off a similar feeling of contemplative stillness. Look for me to count it as one of the year's best in my December roundup. Pop culture profits-prophets? Even Hollywood knows that the fog of war seems less prominent on the battlefield than in conference rooms this time ... so we have two movies about Alexander the Great, a re-imagination on the history of King Arthur and Troy coming out in 2004. All are historical fantasies about the way war lays bare human ambitions, preoccupations and failings. Conveniently, all are set a long time ago. OK, so back in 2001 Hollywood knew the public would be striving for context and/or what real leadership looks like – and it's only now starting to come out. Of course, this is the Hollywood version, so it all will likely be incredibly dumbed down and uber-hyped. I'm certain that the important Bucephalus and Alexandria segments in the Alexander films will be mere vignettes. I wonder if these fantasies will lead to some critical metaphors in the lighter-weight aspects of the U.S. media, like "Access Hollywood," "Today," "Oprah" and film reviews in general. I’m not holding my breath.

Reality is wasted on the realists?

A film like "Lost In Translation" struck a chord last year. Basically, it was a floating fluxy study on being emotionally out of control in Japan. As a study in recapturing one's true essence through the company of strangers, I felt Bill Murray's was the only redeeming character in the film. Without Murray and some wonderfully stylistic cinematography adopted from other films, like "YiYi," it would have been just awful. I think we all knew this and were so glad it threaded the needle. We gave "LIT" too much praise. Actually, can we give a film that takes chances and succeeds too much praise? No ... but that is a problem. The bar has been so lowered that "LIT," which pales even compared to lightweights like "Breakfast at Tiffany's," isn't a revelation. The art world has the same problem ... pick between paintings; a De Kooning or a Cecily Brown.

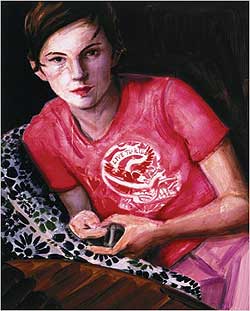

Brown as a painter is good, but De Kooning ate her lunch. Let's also remember super-painter Elizabeth Peyton is friends with "LIT" director Sophia Coppola and probably showed her a thing or two about creating mood. Peyton has been the best painter in the world since at least 1996 and should have been in Dave Hickey's Beau Monde, but I'll take her presence in the 2004 Whitney Biennial as a victory for Hickey, nonetheless. She's the transcendental Norman Rockwell of beauty with Edvard Munch and Edouard Manet lovingly thrown in. In the parallel Rock 'n' Roll Universe, the Strokes video for "Reptilia" basically borrows from Peyton's odd, intimate expressionistic feel and intensely moody color schemes. She paints portraits of the band members all the time, so I doubt that it's mere coincidence. That's another reason she's definitely the best; other genres have found her worth copying. David Hockney should start taking lessons from her. Sure, she learned from him. But at her solo show at Gavin Brown Enterprises in April, she was so wryly hedonistic that she made Hockney look more like Edvard Munch. She's Munch's true antipode. Hockney's been superceded by Peyton, the onetime apprentice. 'Kill

Bill' Like "Lost In Translation," Tarantino's film takes place in Tokyo, but with a diamond-hard, almost cartoony, focus. "Kill Bill Vol. 1" was a genius-level action flick – adrenaline and tongue-in-cheek genre vengeance. But without the guilt of knowing all the details of the grievances between The Bride and Bill, it was just the appetizer compared to "Kill Bill Vol. 2."

"Vol. 2" fills in the blanks and the emotional tangle. Funny, it seems The Bride ditched Bill and faked her death when she found out she was pregnant. Notably, the crucial scene where the two female assassins discuss the implications of a pregnancy test while respectively trying to carry out and avoid a hit is brilliant. It's even better than the "Vol. 1" mommy battle between Vernita Green and Beatrix Kiddo (The Bride). In the pregnancy-test scene, The Bride effectively gets out of the assassin business and into the mommy business. Directly after that scene, Bill, who in his twisted way still loved The Bride, was looking for his beloved's killer, only to catch up with her just before she's about to marry a Texas doofus. The audience kinda understands how he might snap. That doesn't make it right, but we identify both of them as victims. Sadists and masochists are completely interchangeable at a certain level and, when two assassins are about to become parents, their lack of people skills couldn’t be more tragicomic. The wedding rehearsal probably draws on Tarantino, Uma Thurman and Ethan Hawke’s, relationships giving it extra emotional baggage.

David Carradine is worthy of best supporting actor and plays the ultimate bad boyfriend. He's evil and can't do anything about it. Thurman is just as bad, but she is transformed by having a child; she's in no moral position to judge Bill, but being a mommy trumps everything. It's true, nothing on earth is as intimidating or legitimate as a mother and baby. I have to smile every time I see a mother and child, and Thurman's character, although she still has feelings for Bill, just can't have Bill around. Bill's excuse of "I overreacted" for shooting Kiddo was one of film history’s best understatements, yet it rings true to life in dysfunctional trailer parks or the coked-up Hollywood Hills. Bill and Beatrix are professionals; since its called "Kill Bill," Bill has to die. Synopsis: Daddy shot Mommy, so Mommy used the five-point exploding-heart technique to make Daddy go away ... it sure seems to this viewer like an analog of Mommy filed for a divorce with felony abuse charges. We have come a long way since "Kramer vs. Kramer" and we are more professional and wicked about splitting up a family with kids in the middle. It's a vicious circle and I wonder if these broken-home kids become emotional assassins as well. "Kill Bill" is so fake it smacks of honesty ... truth in fiction. More real fakes

David Bowie came to Portland in April and has never been more important, even though in interviews he's resigned himself to no longer being hit-maker central (although that's never really been his lot). He's not Britney Spears, the Strokes or the White Stripes and, of course, that's why he's wrong about his importance. His career is the iconic unattainable dream of every fame-seeker whose management makes "the decisions." Bowie is the antipode; he has control and is the flash in the pan that never goes away. His characters – Ziggy, the Thin White Duke, et al – they all fade. They're designed to fade. However, the ghost of Bowie remains. Precisely, he's more interested in getting away with his own character assassination before others can do it. A lot of arty people age 18-45 have rightly seen this as one of the only sure-fire ways to retain anything with the scent integrity on it. He's sincere about presenting something insincere.

He's an actor playing a rock star, whereas Britney, the Strokes

and the White Stripes are pop and rock stars that would sell

their souls to be actors. Bowie is the one famous artist-type who never seemed capable of losing his soul. The secret? Sell the soul beforehand to reduce that liability potential. Bowie's latest album, Reality, is OK for 2004, but he needs to use recording engineer Steve Albini (PJ Harvey's Rid of Me) to cut out the unnecessary gloss. That rawer sound is part of the reason Bowie's songs with Mick Ronson are often the best, but "Heroes," "Fame," "Let's Dance," and two songs from his most hated Tin Machine project, "I Can't Read" and "Under The God," are some of his very best. "Under Pressure" is a masterpiece, but Freddie Mercury had skills and chutzpah even Bowie envied. Rationalizing irrational fear

Then there is NBC trying to distract us with the ridiculous "10.5" earthquake TV movie May 2. Yes, the West Coast falling into the Pacific Ocean from Seattle to San Diego makes Bin Laden look like a third grader shooting spitwads, but it's a physical impossibility. A big 9.5 is possible, but gargantuan 10.5 quakes can't be generated by the slip faults and relatively short subduction zones here. It's a cathartic, silly and unscientific production that plays on our fears, irrational tolerance of the Baldwin brothers and appetite for spectacle. Then again, So-Cal is expecting a large 7-9 Richter Scale quake in the Mojave Desert in the next six months. From a cathartic fear-management standpoint, Buffy the Vampire Slayer was better with all those monsters constantly disrupting Sunnydale. In art-related terms, local luminary painter Gregory Grennon catches a lot of hell for being a misogynist who explores doubts and fears, but I find his paintings confrontationally cathartic ... kinda like "Kill Bill Vol. 2," as well. Idealism needs to be used judiciously and so does bitterness; Grennon has bitterness down. The secret: don't use irony as a crutch. Frankly, not all art needs to be easygoing. Besides, I like women who don't smooth everything over. Everything is not OK. A little fear keeps everything from growing stale or complacent; it means you give a damn. Lindsay

Bowdoin Key

American Farm should further cement the Haze Gallery legend in Portland by simple virtue of transforming the gallery into a structure suitable for a barn dance. It comes complete with flying udders, glasses of milk, country music, tin-shack siding and enough hay to potentially kill me. I left four times just to keep from uncontrollable sneezing fits. Did I mention there was a longhaired calf as well

that, in its own sweet way, tried to gore several people affiliated

with the gallery? They had it coming. Haze Director Jack Shimko asked me ahead of time, "do you know how to handle a cow?" That set off alarms; Shimko's a city slicker. Me? I've pulled a calf or two in my day, so I can make the Dukes of Hazard distinction. (Translation: I've been a bovine midwife.) That was the scene; now for the art. The overall installation was immersive and the scent alone legitimized the farm. In fact, hay is food to cud-chewing ruminants like the li'l calf present at the opening. In addition, the hamburger I ate definitely connected me to a life-and-death cycle that farmers all understand. Most First-World people outside of farms have precious little idea where their food comes from, producing a calloused arrogance along the food chain. The paintings, with their hungry birds and cows, illustrated this point excessively and really didn't add anything. When a tasty sandwich beats a painting, don't show the painting. Yet Key made a successful point regarding consumption and Americans' desire to not know how the sausage is made.

The real showstopper was her video of fake "Stepford" alpacas amongst the real alpacas. Sure, it calls genetically designed animals into question, but there's more going on here. Key is from Manhattan, a place that rightly has felt under siege since 9/11. New York, by being a huge target, makes one have farm and countryside fantasies. In fact, the fake alpacas could be read as "sleeper terrorists." Key is onto something here and her plan to work with sheep in the Portland area would elegantly consolidate the more fabricated aspects of the American farm into one big, poetic statement. This has great possibilities: counting sheep, wolves in sheep's clothing, and the sticky question about whether Americans are just dull sheep being led to the slaughter by corporations, politicians and terrorists, opens exciting questions. I like the look of this: pop, politics, authentication, terrorism, science and age-old farming ... could be something very impressive. State

of Affairs

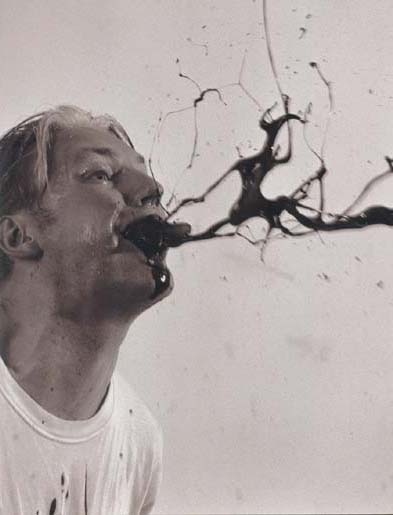

Stuart Horodner is billing his first independent curatorial effort in Portland as "a mood ring of a show" and it's definitely not to be missed, as it mostly refrains from knee-jerk statements. The exhibition begins with one of the more exciting early-'90s Tony Tasset black-and-white photographs, "Spew." As a comment on media hype, oil consumption (it looks like Tasset is spewing oil) and Jackson Pollock's trumping of the European avant-garde, it meditates on situations that were in effect back in 1993, but continue to be bandied about today. The U.S.A.'s dominance of the art world may now be in full retreat since our latest champion, Elizabeth Peyton, has been big since 1996. The point is that "Spew" looks prophetic, and being prophetic after 10 years gives the work a kind of art-historical halo. Sara Masacar's "All Sorts: Heads of State" is a nicely finished installation of tiny licorice leader heads and an accompanying book. Why licorice? It could be the waxy, impermanent nature of the position. I suspect, though, it's more of a dada-esque leveling. This is well done visually, but lacks a denouement to elevate it.

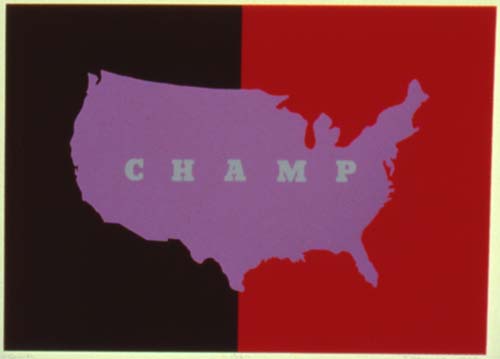

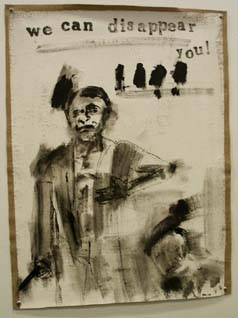

No such problem with Leon Golub, the heavyweight star of this show. His trademark raw canvases tacked to the wall show why he has been the premier social realist artist since George Grosz. His "We Can Disappear You" could apply to government thugs anywhere in the world. Or to terrorist thugs anywhere in the world. The possibilities are indistinguishable. His talent is for bringing out the timelessness in such difficult and time-sensitive imagery. Others who attempt this sort of work make the mistake of being too shrill or tricky. Instead, Golub gives threat a sketchy physical posture and confrontational stance that I've always admired. He draws the viewer in as both a witness and a possible victim. Aside from the message, you know it's good because it pulls people in from across the room. Another star of this show is Tad Savinar. His silkscreen, "Champ," is probably his single best piece. Upon viewing you have to ask: Is the United States still No. 1? Do we deserve the status, or not? It's a multi-layered critique and celebration.

With great power comes great responsibility and, as the only superpower, the U.S. coasted during the '90s. Now we have the same challenges but they are knocking on the door in ways we can no longer ignore. Other works, like John Sparagana's elegantly distressed magazine ads and Michael Bise's satirical cartoons, are nice and current (touching on consumerism and angst-filled neglect of teens, respectively) but will probably be superceded by real comic books and real advertisements that manage to survive for another 300 years as artifact art objects. They live on borrowed cultural force and lack the authority over the subject matter to make the art history books. The same problem exists for Daniel Duford's "Jubilation." Just because his golem has a comic-book quality similar to Paul Chadwick's Concrete character doesn't make this particularly strong work. Besides, the whole golem idea seems like an illustration lifted from Dungeons & Dragons, only without its deep roots in Jewish folklore being developed or expanded enough to be remotely successful.

Without the oomph of George Grosz or Leon Golub, the "Jubilation" golem seems akin to high-school anti-war murals. Mary Shelley's Frankenstein did it so much better, creating both empathy and terror. Even the celebrating Fallujah-ers seemed compositionally tacked on. It's agitprop and, although I liked how the drawing addressed the industrial service door, it lacked style. Duford is talented but he hasn't learned the importance of being more than earnest. Barbara Pollock's "American Army" video was a definite highlight. In the piece, we watch a young man play a video game designed as a recruitment tool for the U.S. Army. With the young man on the split screen above and the video-game action below, it certainly is a study in strange ambivalence – one where the video-game player probably gets a less consequential dose of reality, which possibly innoculates him from the true price of war.

When the video-game soldier is shot, the player spins his third-person camera up and around the eerie scene. The mood is somber and impassive. For something closer to civilian life, Marne Lucas' self-portraits with mirrors and other reflections are less impassive and more revealing. Sometimes she's sexy, sometimes it looks like Velazquez's "Las Meninas" with a cast of court players playing out roles. I don't know the people, so it's difficult to decode. At other times, like her turn at impersonating a zoot-suited boy, she questions how she is defined and records it like a memory as a secondary image. Oh yes, a defiant boy is just being a bad boy. But a defiant girl is still largely unacceptable. None of this is new, but that's not the point. Maybe it's how things haven't changed that tells us most about the state of affairs of American life in 2004. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

E-mail Jeff at pivotofjade@hotmail.com, don’t miss his recent columns

and be sure to see his April 2002 essay, Art and Threat: Untaming

Humanism.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|